Unlocking Relief: Effective Strategies for Understanding and Working Out with Non-Specific Low Back Pain (LBP)

December 2024

Have you ever woken up with stiffness in your lower back? Or noticed it tightening up after hours at a desk or behind the wheel? You're not alone—at least 80% of people will experience some form of lower back pain (LBP) in their lifetime (Freburger et al., 2015). If you’re reading this, there’s a good chance you are part of that 80%. This article will focus on non-specific LBP—pain that has no link to a specific cause, diagnosis, or pathology. LBP can be both physically and mentally debilitating, but there are effective options beyond just medications or prolonged rest. Exercise is medicine, and motion is lotion; your body WANTS to move. The key is learning how to do so safely and effectively, respecting the limits of your current LBP.

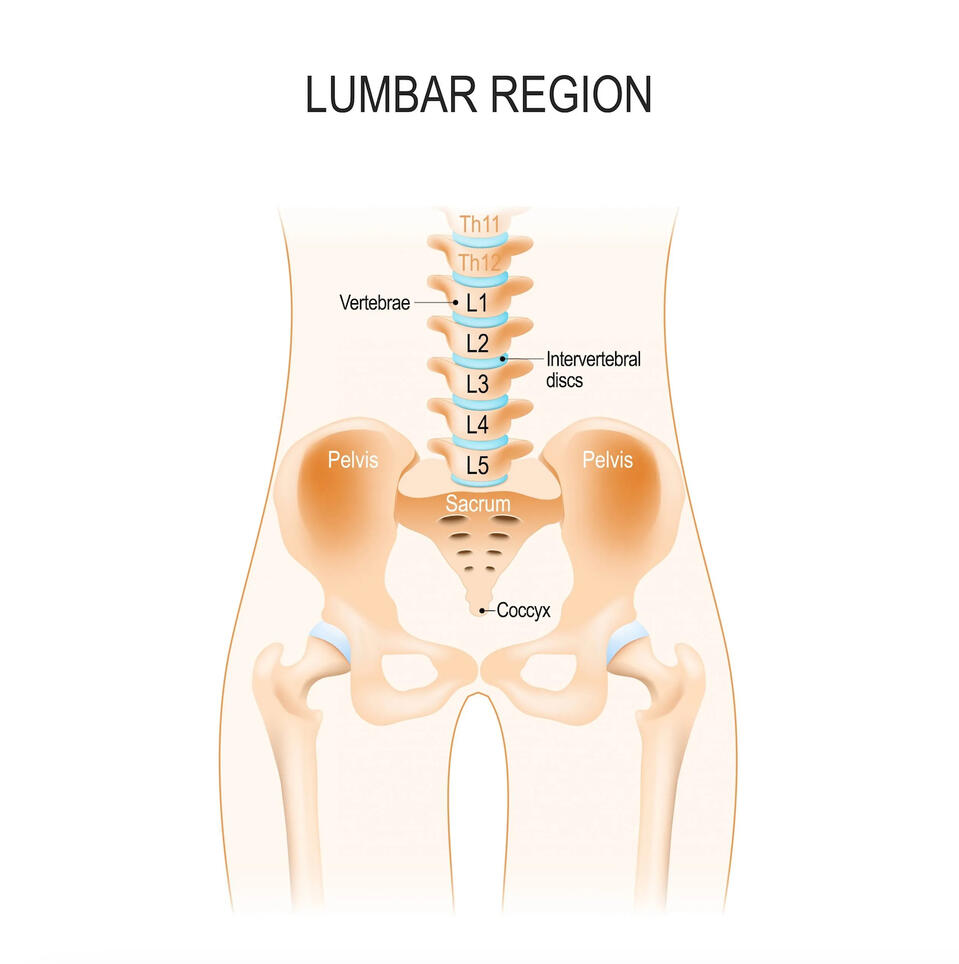

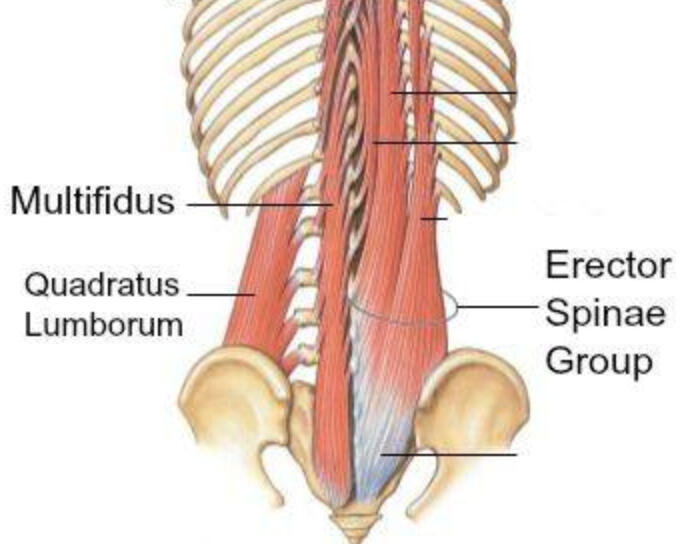

First, let’s dive into the anatomy of the lower back. The lower back, or lumbar spine, consists of five vertebrae labeled L1 through L5. The lumbar spine joins to the hip bones via the sacrum, creating your pelvis. Some key muscles in the lower back include the Quadratus Lumborum (QL), the Erector Spinae, and the Multifidus. The QL attaches to the lumbar spine, hips, and lowest ribs, and plays a vital role in side bending, exhalation, stabilizing the hips and lower back, and hiking the hip. The Erector Spinae muscles run along the entire spine, helping to stabilize it and keep you upright, particularly when bending or hinging forward. The Multifidus, a deeper muscle, is essential for spinal stability.

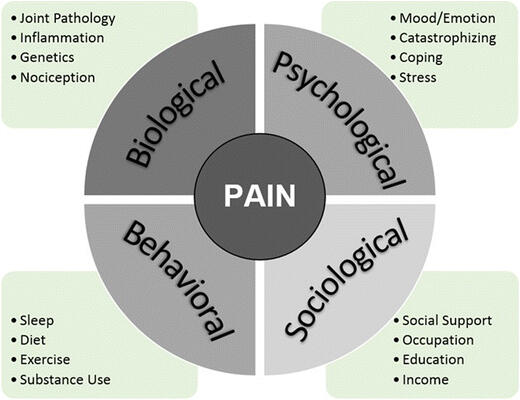

Non-specific LBP is a complex issue; and focusing only on the lower back may yield some improvement. However, addressing deficits and limitations in the surrounding areas—like the pelvis, hips, and ribcage—as well as considering biopsychosocial factors (such as work stress, lifestyle habits, negative beliefs about LBP, and fear of movement) can lead to more effective, long-term management. You always want to reverse engineer the process, and ask yourself why is your back hurting in the first place.

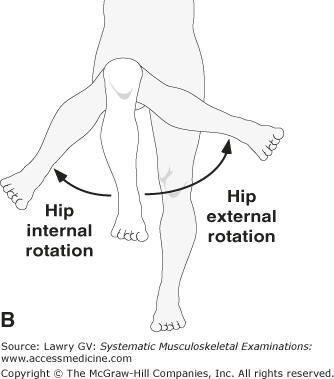

A systematic review by Avman et al., 2019 titled, “Is there an association between hip range of motion and nonspecific low back pain?” analyzed studies comparing all measures of hip ranges of motion - hip flexion, extension, hip internal rotation, hip external rotation, hip abduction, hip adduction - in individuals with non-specific LBP. The majority of studies (10/14) showed a tendency for a limitation of internal rotation (IR) range of motion (ROM) in individuals with non-specific LBP, with five studies reaching significance (Avman et al., 2019). Improving hip IR has been a criterion associated with improvement in non-specific LBP, but understanding why is key.

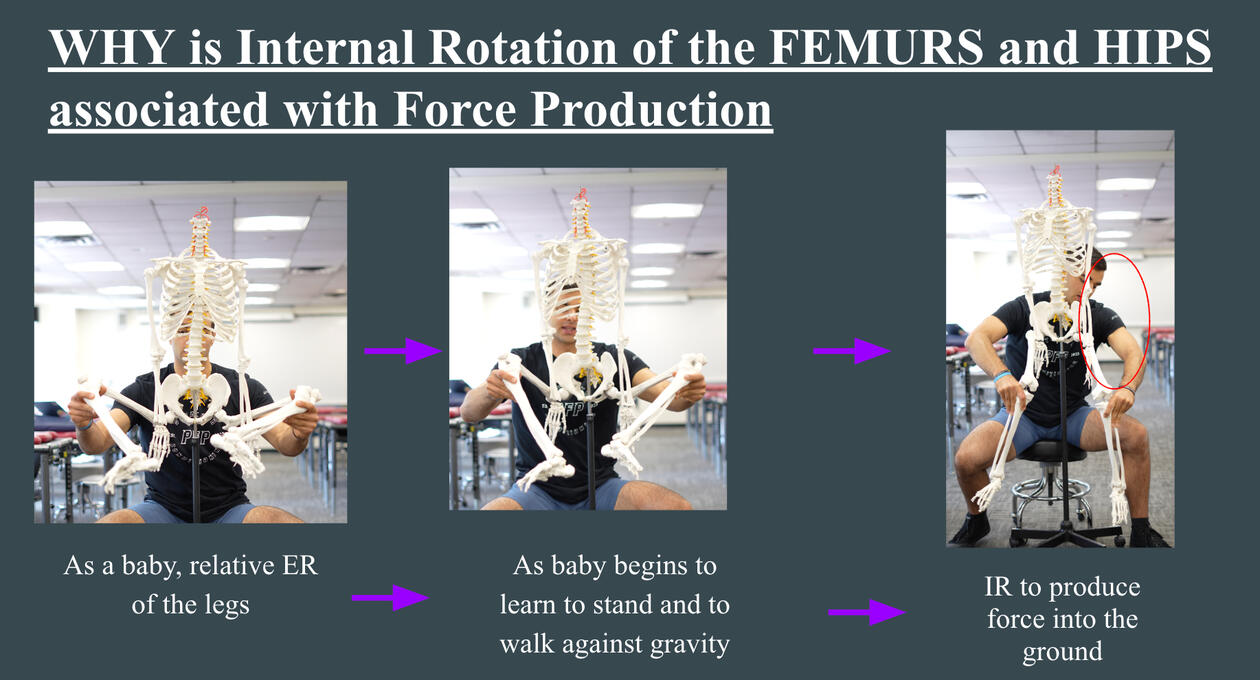

Picture a frog in water - look how the legs are externally rotated to better suit the mode of locomotion in that environment - swimming. There's no need to produce force into the ground. What does a frog have to do with my LBP? Stick with us for a second.When a baby develops in the womb, surrounded by water and fluid, there’s no need to push against the ground. The lower limbs are highly externally rotated; this leg positioning is still visible in the first months after birth, especially when the baby is lying on his or her back. Once the child starts pulling to stand and walking, the legs rotate inward in order to push into the ground. This shift toward internal rotation (IR) is essential for producing ground force.For individuals with non-specific LBP, restoring this IR range of motion is critical. Without sufficient IR, it becomes harder to push forcefully into the ground, leaving the structures of the lower back to compensate by constantly stabilizing during standing and walking. Add in external loads during exercise, and without adequate force production capabilities, the risk of injury rises significantly.

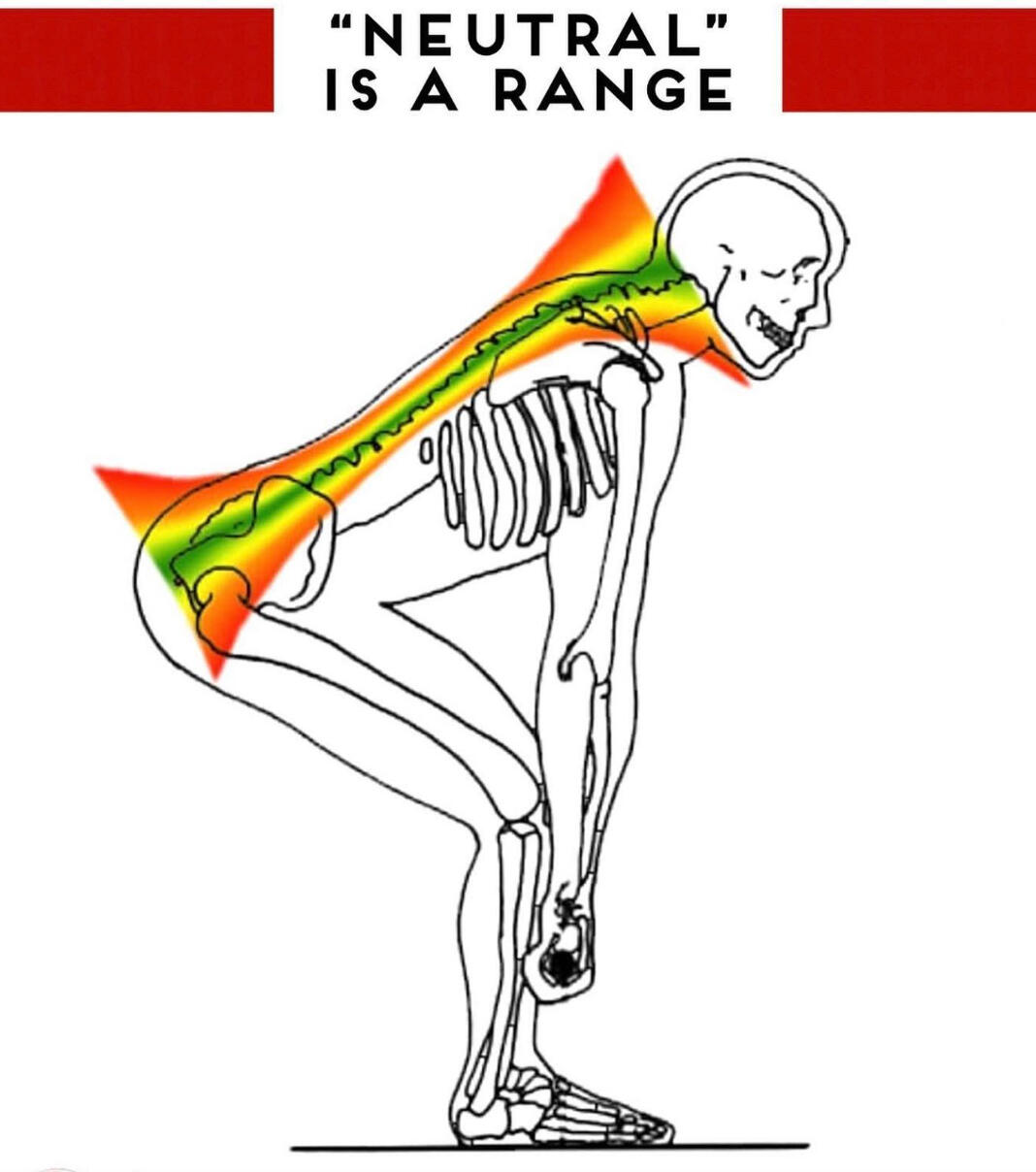

Let’s say we cleaned up that hip ROM and restored all movement options needed at the hips and pelvis. We need to address the actual position of the lumbar spine when performing exercises to ensure confidence, safety, and proper technique when lifting. There’s a lot of conflicting advice about the “correct” way to position the lower back during workouts. Some argue against lumbar flexion (a rounded back), associating it solely with the risk of disc herniations. Many still believe that lifting with a flexed lumbar spine is a primary cause of lifting-related low back pain (LBP). A recent systematic review by Saraceni et al., 2020 challenged this notion. Out of the 11 studies included in the systematic review, 9 found no prospective association between lumbar spine flexion when lifting and the development of significantly disabling LBP (Saraceni et al., 2020). This study proved that current advice to avoid lumbar flexion during lifting to reduce LBP risk is not evidence-based.

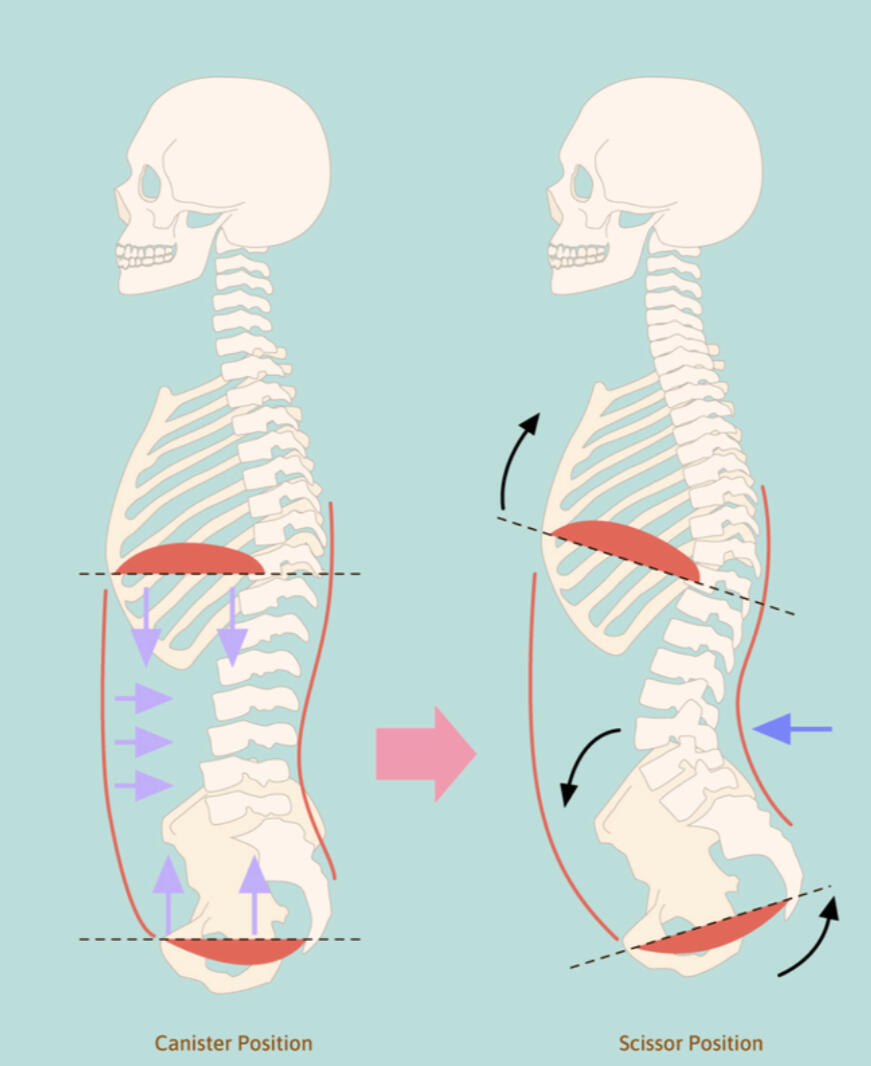

Some will advocate for a “neutral” or slightly arched lordotic curve. Let’s first start on the word “neutral.” How can one even objectively quantify what a “neutral” spine looks like? A “neutral” spine involves more of a refers to a range within which the client, athlete, or patient is not at either extreme of lumbar movement (not overly rounded or excessively arched). Maintaining a pronounced lordotic curve, however, can pose multiple issues.First, it often creates an anterior pelvic tilt (APT), associated with extension tone and a “fight or flight” state; this locks up the pelvis and decreases relative motions needed to be able to move.Secondly, an APT decreases hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation ranges of motion, quickly restricting hip mobility. This limitation forces the lower back to compensate to reach deeper positions in squats, hip hinges, or other lower-body movements.Lastly, it does not adequately keep the ribcage stacked on top of the pelvis, creating inefficient breathing and bracing mechanics while trying to manage heavy external loads.

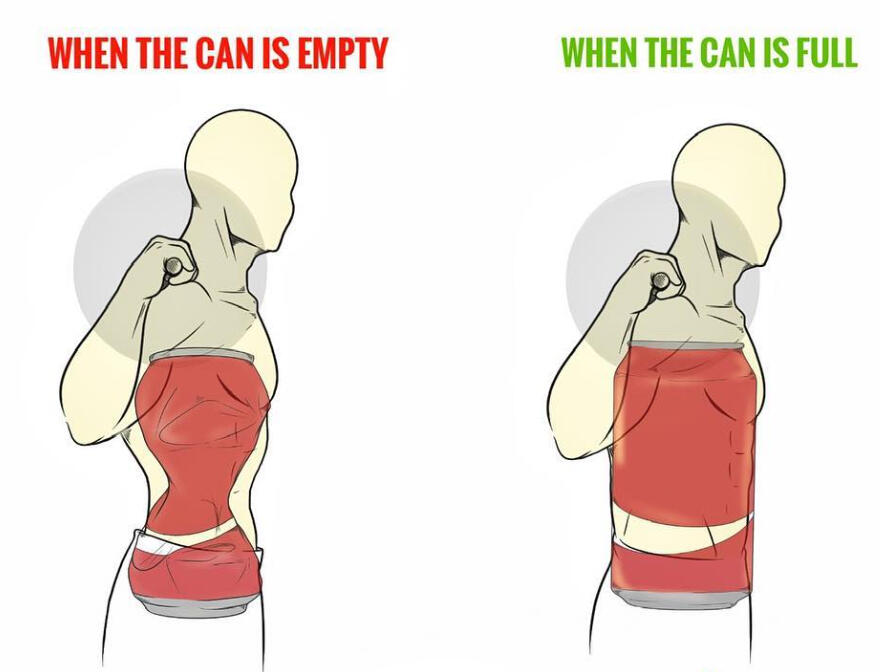

Whatever starting position you put yourself in, you need to be able to stabilize and to create enough internal pressures to maintain that spinal alignment. Problems start coming in when the load you are lifting exceeds the amount of internal pressure you can generate to stabilize effectively. In this situation, the lumbar spine may start to deviate from the starting position or move while under load, which can lead to issues if repeated frequently or with heavy loads.

To create maximum internal pressure, you will need to be able to stack the ribcage on top of the pelvis. Start by exhaling fully through pursed lips, as if blowing out a birthday candle, or use an open-mouthed sigh as if fogging up a window. This closes down the rib cage, inflares or turns your hip bones inward slightly, and engages your side abs. This generates significant intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) to press against and obtains the relative motion at the hips needed to direct force from the lower body directly into the ground. Maintaining this side-ab tension while inhaling and bracing by pushing the side abs outward (rather than the belly forward) increases torso and lower back stability.To demonstrate just how important breathing is, a study examining diaphragm function in elite weightlifters with and without chronic low back pain (LBP) revealed that those with chronic LBP showed reduced diaphragm contractility compared to their pain-free counterparts (Zhou et al., 2024). The study also discovered that the diaphragm’s strength correlates strongly with lifting performance (Zhou et al., 2024). Like trying to step on an unopened soda can, a pressurized system can withstand greater external loads.

Humans are not fragile, we are antifragile. We just need to match the loads we are working with to the ability we can stabilize our lower back and trunk and then gradually progress from there. For those individuals with a history of LBP, starting slow and progressively performing exercises suited to his or her current skill level—with proper core stabilization—provides tangible proof that the individual can handle the movement and external load safely. Over time, this approach builds the confidence and competence needed to move more, to gradually and safely increase load, to get stronger, to train consistently, and to build a more resilient body for the long term. Getting stronger and staying healthy simultaneously is our PFP standard.